By Verena Engel, MSc. Candidate, Bauhaus-University Weimar

Cycling has many personal benefits: increased health and fitness, reduced stress, time savings, or lower transportation costs are some examples. Beyond that, larger economic and societal benefits can be attained on a municipal or regional scale if the cycling mode share increases. These include lower maintenance and construction costs for urban streets, increased business revenues, reduced health care expenditures, a decrease in traffic congestion, an enhancement of street safety and security, as well as more accessible, livable, and connected communities. That is why investments in bike lanes are desirable for cities all over the world.

Vancouver has started to take advantage of this potential and gained an international reputation as a cycling city. Through an extension of the bicycle network, cycling in Vancouver increased by 3.5 times in just eleven years - from 2% in 2006 to 6.9% in 20171. Especially investments in protected bike lanes have proven to be an effective means to increase the cycling mode share in North American cities, Europe, and Australia. Protected bike lanes physically separate cyclists from fast motorized traffic. This increases the actual and perceived road safety for cyclists, along with the level of comfort for a variety of people, and leads to a higher cycling mode share. An evaluation of protected bike lanes in the U.S., for example, revealed that 85% of people that are interested in cycling but have safety concerns, would be more likely to bike if there was a physical barrier between cars and bikes2. In Vancouver, 56% of residents want to cycle more3, but almost half of the Vancouver population have safety concerns. Hence, there is a vast potential for more cycling in Vancouver.

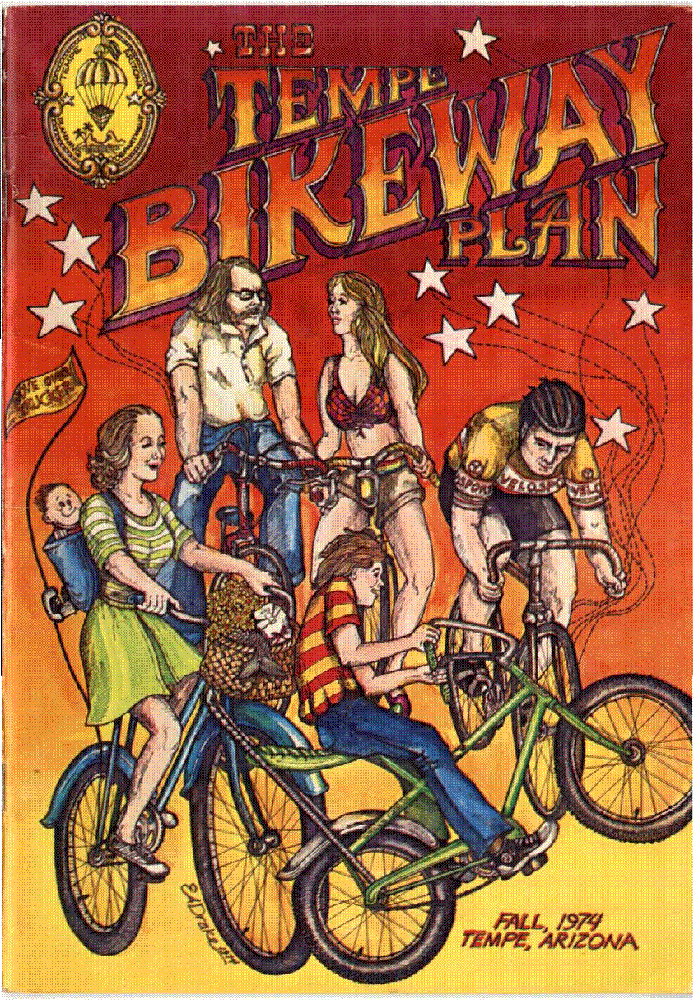

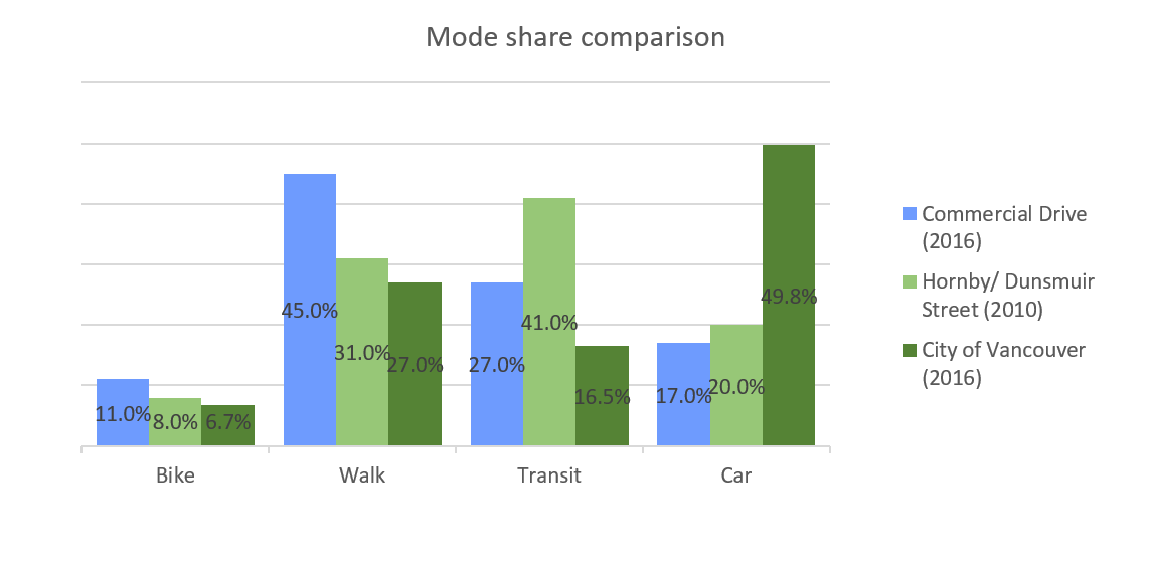

In theory, a lot of non-work trips could be done by bike instead of car because they tend to be a lot shorter than commuting trips. Practically, though, most of the current bike trips made in Vancouver are for work or school purposes (see Figure 1). This is not so surprising, considering that most of the protected bicycle infrastructure in Vancouver is targeted towards cycling commuters. It also means that a large potential of more cycling for other purposes is left untouched.

Figure 1 - Mode Share per Trip Purpose in the City of Vancouver, 20174

Figure 1 - Mode Share per Trip Purpose in the City of Vancouver, 20174

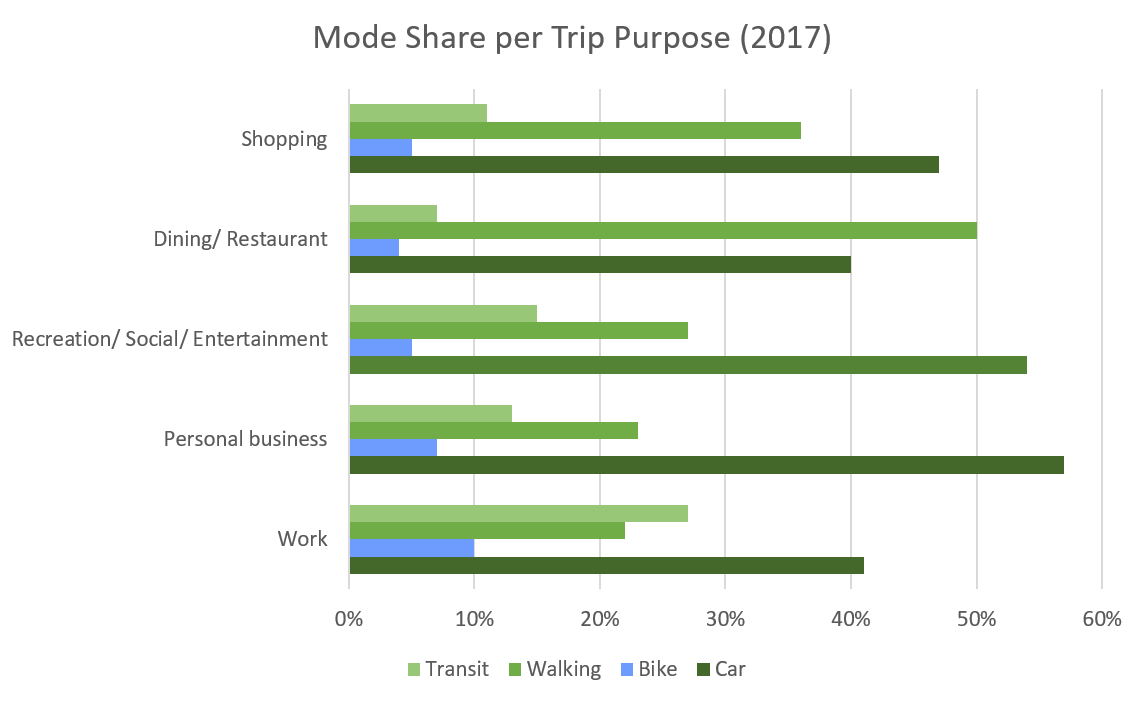

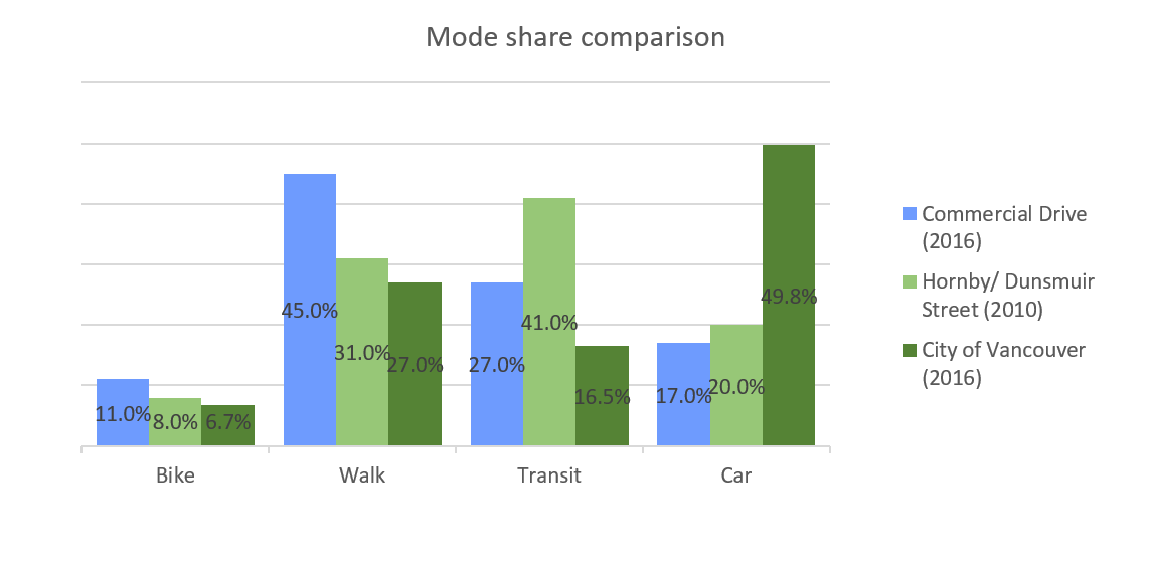

So what can be done to fulfill this potential? If trips to recreational activities or to run errands should be done by bike, relevant destinations need to be accessible by bike in a safe and comfortable way. This might seem simple, but outside of downtown no businesses and services on commercial high streets can be directly accessed via any sort of bike lane. Some of the commercial high streets are indeed amongst the most dangerous streets to bike on in the City of Vancouver5. And still, there are far more people arriving by foot and bike there than on other streets (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Mode share comparison between a commercial high street, downtown, and city context6

Figure 2 - Mode share comparison between a commercial high street, downtown, and city context6

As mentioned earlier, this share could be significantly higher – meaning less cars, less noise, and more safety on our local shopping streets. However, the lack of proper cycling infrastructure is a barrier to cycling for many people: The number of people feeling comfortable cycling on major streets with protected bike lanes is almost 4 times higher than the number of people that feel comfortable biking on major streets without any bike lanes7. An implementation of protected bike lanes on commercial high streets could benefit people who currently bike on commercial high streets and would also encourage people with present safety concerns to bike for non-commuting trips. Given that more than 40% of the PM rush hour traffic trips are for non-commuting purpose8, this could also reduce traffic congestion on commercial high streets and benefit car drivers.

These are not the only benefits of protected bike lanes on commercial high streets, though. And, of course, there are also some risks that need to be mitigated. A recent study assessed current circumstances that positively and negatively affect an implementation of this type of infrastructure, along with expected opportunities and threats. Some of the most interesting findings are briefly summarized below:

The strengths

There is a high existing demand for protected bike lanes on commercial high streets by current and potential cyclists. Furthermore, commercial high streets are highly suitable locations for bicycle infrastructure. HUB Cycling and the City of Vancouver have identified these streets to be amongst the major gaps in the cycling network due to deficiencies of safety, access to destinations, and the completeness of the bike network. Bike routes on these main streets would be the most logical and direct routes that ease navigation through the city by bike. Lighting, visibility, grade and pavement are mostly better than on residential street bikeways already. Hence, protected bike lanes on commercial high streets could be high quality bike routes in the city.

The weaknesses

The perception of cycling in Vancouver complicates a cycling uptake: A lot of people cannot imagine themselves biking because they don’t know how or think it’s too unsafe. Indeed, cyclists that we see in the city are often from a similar demographic background, look rather sporty and use some kind of special cycling equipment. Many people in Vancouver cannot identify with this image. However, if you take a closer look, you can find people of all ages casually biking off our main streets. Hence, if more people biked on highly visible streets like commercial high streets, this could be changed. Another weakness is that several groups might be under- or misrepresented in the planning and decision-making process. Some business owners in Vancouver, for example, do not agree with how they are publicly represented. These public statements have a high influence on some of the projects, though. If infrastructure should be built with the goal of being suitable for as many people as possible, a more accurate representation of the people who are directly or indirectly concerned has to be ensured.

Figure 3 - 'Typical' cyclist in Vancouver

Figure 3 - 'Typical' cyclist in Vancouver

The opportunities

A negative impact on local businesses is amongst the main arguments against protected bike lanes on commercial high streets. However, a negative effect on businesses was found to be highly unlikely. On the contrary – international and local research has shown that in most cases businesses can expect increased foot traffic and revenues. Bike lanes create a more pleasant public realm that attracts more visitors and presents a competitive advantage against online shopping. Besides, bikes are more space efficient than cars when considering travel lanes and parking space. So, the existing road space can cater to more people if it is dedicated to bikes instead of cars. Moreover, through lower costs, skill requirement, and a higher comfort level, bikes are a more accessible means of transport than cars for many people. Biking can also solve transit challenges like the first-and-last-mile problem, especially when protected bike lanes are provided near transit stations – which are often located on commercial high streets – and in conjunction with a public bike share system. The other way around, transit can promote cycling when distances are longer. This is especially relevant with increasing commute distances and other individual transportation needs. Beyond an increase in local business revenues, citizen mobility and bike-transit synergies, protected bike lanes on commercial high streets have the potential to enhance road safety for all road users and create a higher liveability and more opportunities for social interaction.

The threats

Commercial high streets are amongst the main traffic arteries in the city. While fears of increased traffic congestion generally do not materialize, the limited space that is available can raise design challenges. Safety hazards at conflict zones like intersections or driveways have to be avoided and transit punctuality ensured. However, lots of research is currently being conducted to provide design guidance and solutions for these issues. Another concern is the generally existing fear of change. Along with unsuitable practices of public engagement, such as wrong expectations and a skewed population representation, negative political sentiments can be created. Public participation processes are very important and should be appropriate to ensure that newly built infrastructure suits many people’s needs.

Protected bike lanes are a fairly new phenomenon, which makes some citizens and decision-makers nervous because experiences with them are limited. This is a widespread phenomenon, though, so options for safe and functional design are being explored and discussed in many places. Design guidelines are therefore being developed rapidly and internationally, especially in North American cities like Vancouver. They currently lead the way regarding protected bike lanes and even became role models for European cities with a much stronger cycling culture. Let’s show them how it can be done!

1McElhanney Consulting Services Ltd., Mustel Group (2018): 2017 Vancouver Panel Survey. Summary

Report. City of Vancouver. Available online at https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/2017-transportation-

panel-survey-final-draft-20180516.pdf, checked on 9/9/2018.; EPOMM: TEMS - The EPOMM Modal Split Tool. epomm.eu. Available online at http://www.epomm.eu/tems/result_city.phtml?city=274&list=1, checked on 9/10/2018.; City of Vancouver (2018): Walking + Cycling in Vancouver. 2017 Report Card. Vancouver. Available

online at https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/cycling-report-card-2017.pdf, checked on 1/10/2019.

2Monsere, Christopher; Dill, Jennifer; McNeil, Nathan; Clifton, Kelly; Foster, Nick; Goddard, Tara et al. (2014): Lessons from the Green Lanes. Evaluating Protected Bike Lanes in the U.S: Portland State University Library.

3City of Vancouver (2018): Walking + Cycling in Vancouver. 2017 Report Card. Vancouver. Available online at https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/cycling-report-card-2017.pdf, checked on 1/10/2019.

4McElhanney Consulting Services Ltd., Mustel Group (2018): 2017 Vancouver Panel Survey. Summary

Report. City of Vancouver. Available online at https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/2017-transportation-

panel-survey-final-draft-20180516.pdf, checked on 9/9/2018.

5City of Vancouver (2015): Cycling Safety Study. Final Report. With assistance of Urban Systems, CyclingInCities.

6City of Vancouver (2016): Commercial Drive Complete Street. Available online at https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/commercial-drive-complete-street-display-boards-oct2016.pdf,

checked on 11/14/2018.; McElhanney Consulting Services Ltd., Mustel Group (2017): 2016 Vancouver Panel Survey. Summary Report. Edited by City of Vancouver. Vancouver. Available online at http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/transportation-panel-survey-2016-final-report.pdf, checked on 5/25/2018.; Stantec (2011): Vancouver Separated Bike Lane Business Impact Study. With assistance of Stantec Consulting Ltd. with Site Economics and Mustel Group Market Research. Edited by Vancouver Economic Development Commission, City of Vancouver, Downtown Vancouver Association, Downtown Vancouver Business Impact Improvement Association, The Vancouver Board of Trade. Vancouver. Available online at http://council.vancouver.ca/20110728/documents/penv3-BusinessImpactStudyReportDowntownSeparatedBicycleLanes-StantecReport.pdf, checked on 5/22/2018.

7McElhanney Consulting Services Ltd., Mustel Group (2018): 2017 Vancouver Panel Survey. Summary

Report. City of Vancouver. Available online at https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/2017-transportation-

panel-survey-final-draft-20180516.pdf, checked on 9/9/2018.

8National Complete Streets Coalition: Complete Streets Ease Traffic Woes. Implementing complete streets. With assistance of Smart Growth America, National Complete Streets Coalition. Washington DC.; TransLink (2013): 2011 Metro Vancouver Regional Trip Diary Survey. Analysis Report. Available online at https://www.translink.ca/-/media/Documents/customer_info/translink_listens/customer_surveys/trip_diaries/2011-Metro-

Vancouver-Regional-Trip-Diary--Analysis-Report.pdf, checked on 8/6/2018.

Figure 1 - Mode Share per Trip Purpose in the City of Vancouver, 20174

Figure 1 - Mode Share per Trip Purpose in the City of Vancouver, 20174 Figure 2 - Mode share comparison between a commercial high street, downtown, and city context6

Figure 2 - Mode share comparison between a commercial high street, downtown, and city context6 Figure 3 - 'Typical' cyclist in Vancouver

Figure 3 - 'Typical' cyclist in Vancouver